Qualitative Methodology

For any researcher completing qualitative research and analysis, your primary goal in the methodology chapter is to provide a clear and convincing argument for using your selected qualitative design. This includes how to conduct this type of qualitative research, its strengths and weaknesses, and research questions clearly aligned with your chosen qualitative method.

Hopefully, you’ve already ensured that your foundational elements clearly align with a qualitative methodology during the topic development phase. However, even if you’ve only completed a rough outline toward your qualitative research design, we can help you finalize your full methodology section so that each step of your proposed research is defined, aligned, and ready for approval.

There are 3 ways to initiate contact with us:

- Please review and submit the following form. Someone from our team will contact you within 1 hour (during business hours), or at your requested time.

- Our consulting team is available via telephone Monday through Saturday from 8:00 A.M. to 8:00 P.M Eastern Time. Feel free to call us on (702) 708-1411!

- We also pride ourselves on our very prompt and in-depth e-mail responses, 365 days per year. We normally answer all urgent queries very promptly, including late-night and weekend requests. You can email us at Info@PrecisionConsultingCompany.com

Please be prepared to discuss the specifics of your project, your timeline for assistance, and any other relevant information regarding your proposed consultation. We respect the confidentiality of your project and will, at your request, supply you with a Non-Disclosure Agreement before discussing specifics.

When you complete qualitative research, your focus during data collection (and eventual analysis) is based on language rather than numerical data. In other words, instead of using statistical analysis to make sense of numerical data, you follow a systematic language-centered analysis technique to make sense of various forms of data that are not quantified. This is why one very common form of data collection takes the form of interviews with participants, which are then transcribed for qualitative analysis.

Because you’re not limited by survey instruments with a fixed set of possible responses (note: if this does describe your study instrument, please visit our quantitative methods page), you can collect data on all kinds of topics in a very flexible and open-ended manner. You can also explore the complexity of participants’ inner thoughts and interpretations, including their perceptions of factors that have influenced them to think or behave in certain ways. This makes qualitative research and analysis great for exploring understudied topics or learning about the variability in participants’ perspectives–without being constrained by a statistician’s focus on central tendencies in the data.

At Precision, we offer the most comprehensive dissertation consulting and drafting support for both beginning and experienced researchers completing qualitative research. We even support researchers completing mixed-methods studies, particularly in the medical field, drawing on our dual experience with statistical and qualitative research.

If you’re completing qualitative research, we can absolutely help you finalize your methodology chapter–we can even complete your analysis (using NVivo or any other qualitative analysis software) once you’ve completed your data collection. We’ll even remain with you for any revisions, to make sure you succeed.

- First, we provide a detailed explanation of your research design, including why the selection of your chosen qualitative research approach is best to investigate your particular research questions exploring participants’ experiences of a particular phenomenon. As with the literature review, this chapter will incorporate references to established researchers and research methods to prove the credibility of your specific methodology.

- After discussing your research design in detail, we then help you develop a full discussion of your target population and sampling strategy, describing your process for recruiting participants as well as the optimal number to ensure a robust qualitative analysis and results discussion. We also explain and justify your data collection methods during the interview process.

- Based on your selected design, we then identify the best qualitative analysis protocol for your study. Our extensive experience with the five major qualitative research methodologies means we’ll help you identify the best approach to fully investigate your research questions, and then describe stage of the appropriate analysis protocol in detail.

- Finally, we address all ethical considerations and potential limitations for your study, such as your assumptions as a researcher, and the credibility, confirmability, and replicability of your qualitative research data–ensuring a smooth path through IRB approval. For this step and every aspect of your methodology chapter, we remain with you for unlimited revisions to our work.

Let’s keep it a secret…

Before sharing your materials with us, we will send you our Non-Disclosure Agreement, which guarantees that your work materials, and even your identity as a client, will never be shared with a third party.Hi! Are you thinking about using a qualitative approach for your dissertation research?

Maybe you’ve heard some neat things about qualitative research but you’re not sure if it’s the right choice for your study. It is important to understand what exactly a qualitative research approach entails in order to make an informed decision on whether it’s right for your study. This includes how to conduct this type of research, what its strengths and weaknesses are, and what kinds of research questions you can and cannot answer using this method. Many of our clients call upon us for help with their qualitative dissertations and thesis research, and it really is a very powerful method when you know how to use it appropriately.

In this video, I’ll explain the rationale for using a qualitative method in your study, or in other words, when this approach is a good idea and when it’s not for your study. I’ll also help you understand the differences between a handful of research designs that are compatible with the qualitative paradigm, so that you can pick out the best one for your particular study. Assisting thesis and doctoral candidates with qualitative research — from setting up your methodology through qualitative analysis — is a very common form of dissertation help we provide. I hope you’ll find this instructional video helpful as you consider whether and how to use a qualitative method in your own study.

I should mention that having a solid research gap aligned with a qualitative approach will be important as a first step, so check out our video on topic development if you’re still working through that stage!

So, before I talk about the different types of research designs within the qualitative paradigm, let’s first talk about the rationale for using this method in your study.

When writing up the methods sections of your thesis or dissertation, you will have to be able to provide a clear and convincing argument for using a qualitative method in your study.

You will need to be able to show your chair and committee that you fully understand what a qualitative method can and cannot do, and you do this by comparing and contrasting qualitative and quantitative methods. In this discussion, you must be able to explain the strengths and weaknesses of a qualitative method, and then explain why a qualitative approach is appropriate, given what you intend to examine in your study.

To help understand the strengths and weaknesses of a qualitative method, it will be helpful to first discuss what exactly is meant when we say “qualitative method.”

When you use a qualitative approach, your analysis is language-based rather than numerical. This means that instead of using statistical analysis to make sense of data that are numerical, you are using a systematic language-centered analysis technique to make sense of various forms of data that are not quantified.

So, one very common form of qualitative data is derived through interviews with participants, which are then transcribed to allow for analysis.

However, qualitative data may also include written notes that are based on more or less structured observations, archival documents like newspaper stories or clinical history narratives, or even text drawn from sources like film or song lyrics.

Now, I’m sure you can see how analyzing pages and pages of interview transcripts would require a different approach than would be used to analyze the answers to surveys that use numerical scales, like the Likert-type scales that are so commonly used in survey research. Let’s now compare and contrast qualitative and quantitative methods, to give you a sense of what is right for your study.

As you will see, the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative and quantitative methods are complementary, which is why some researchers choose to use a mixed methods approach. Check out our instructional video on this to learn more. But, to focus on the strengths of these methods first, let’s consider the strengths of a quantitative approach. These are: You can determine the statistical relationships between variables. Because the numerical data are comparatively easy to analyze, you are not limited in your sample size. This allows you to use large samples of randomly selected participants, which then allows you to confidently generalize your results to the broader population this sample represents.

These are some considerable strengths, but qualitative methods can actually do some things that quantitative cannot.

Qualitative methodology is one of our core specialties, and so we can definitely help you to see the unique strengths such a method can bring to your dissertation or thesis research.

For example, because you are not limited by use of survey instruments with only a certain set of possible responses, you can collect data on all kinds of topics in a very flexible and open-ended manner. This makes a qualitative approach great for exploring understudied topics, or for learning about the variability in participants’ perspectives without being constrained by statistical analyses’ focus on central tendencies in the data. You can also explore the complexity of participants’ inner thoughts and interpretations, including their perceptions of factors that have influenced them to think or behave in certain ways; these things are quite hard to get at with a survey.

Of course, with the huge amount of data that results from interviewing participants at length, you are necessarily limited in some ways:

First is the size of sample you can use in a qualitative study. This is one of the primary weaknesses of this approach, as you can never assume that your findings from a qualitative study generalize to the broader population.

This might be a daunting limitation to consider, but quantitative methods are not without their drawbacks as well.

For example, for the types of statistical analysis that master’s and doctoral students are typically most comfortable using, unless you set up your design to ferret out causality between variables, you really cannot make any assumptions about the direction of effects between your variables. Also, you might notice in your survey data that certain participants were outliers, meaning their responses were quite divergent from the mean or median. But, because surveys are closed-choice, you really can’t get at the reasons for those divergent responses, which you can address when you interview participants in an open-ended manner in qualitative studies.

In the course of the dissertation help we provide in relation to methodological choices, however, we find that it is always important to back up and carefully consider what it is you want to study.

So, let’s talk about a couple of examples here to help clarify the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative versus quantitative methods. Imagine that you are interested in learning about why nurses in rural areas have such high turnover. You have established in your problem statement that a shortage of nurses in rural areas might have implications for patient health in these areas, due to lack of consistent and qualified care. So, you want to understand more about turnover in rural nurses to help address the shortage in these areas.

Maybe you find in a review of the literature that nurse retention is correlated with pay, and you think that there is sufficient reason to question whether lower pay in rural areas causes nurses to leave their jobs in search of the higher paying positions in urban areas. OK, great question. Now, how do you approach this?

If you want to get a “big picture” view of what’s happening, say, in the US or Canada with rural nurses and their pay, you would want to use a very large sample, wouldn’t you? If you used a small sample, you would have absolutely no confidence that the relationship between pay and turnover is meaningful beyond that sample.

So, this would likely point you in the direction of a large-sample quantitative study, which turns out great when you discover that nurse pay and turnover are significantly associated and that nurse pay in rural areas is significantly less than in urban areas. You could reasonably suggest that low pay causes nurses in rural areas to leave their jobs, but with so many other factors to consider, and the fact that you only discovered correlations here, you cannot really say for certain that pay causes turnover decisions.

Now, with a qualitative approach, you cannot draw general conclusions about the relative pay of rural nurses compared with urban nurses, nor can you conclude with confidence that pay is associated with turnover across the population of nurses you are studying.

But, what you can do in qualitative research is explore in an open-ended way the first-hand accounts of a small group of rural nurses who left their jobs about their decision-making processes here.

As you might imagine, these interviews could turn up a range of reasons, and maybe even a collection of reasons for deciding to leave that your large scale correlational study couldn’t get at. Maybe there are issues of low pay combined with other challenges of being a rural nurse that eventually led to these professionals choosing to leave their jobs. Maybe some had long commutes, or wanted to work in areas with a greater range of medical specialties and expertise.

Conducting an open-ended exploration of reasons for leaving will clearly provide you with a much richer range of perspectives, as well as first-hand accounts of the causal factors involved in rural nurses’ decisions to move on.

Hopefully this clarifies why you might want to choose a qualitative method or a quantitative one. But, if you would like more personalized help with your dissertation in terms of deciding which method is best for you, give us a call or send an email to ask about this. With our great familiarity with the major online universities, we can help you to select and develop a qualitative methodology that we know will meet the high standards of these schools.

For both beginning and experienced researchers completing qualitative research, we offer the most comprehensive dissertation consulting qualitative studies. So, we can absolutely assist you as you finalize your methodology and complete your analysis. We can help you to figure out whether a qualitative or quantitative method is right for you, talk about what each entails in greater detail, and also assist you to select the most fitting design if you decide on a qualitative research method. And, for master’s and doctoral students who are most likely very new to qualitative research, we’ll stick with you through any revisions required by your schools to make sure you succeed.

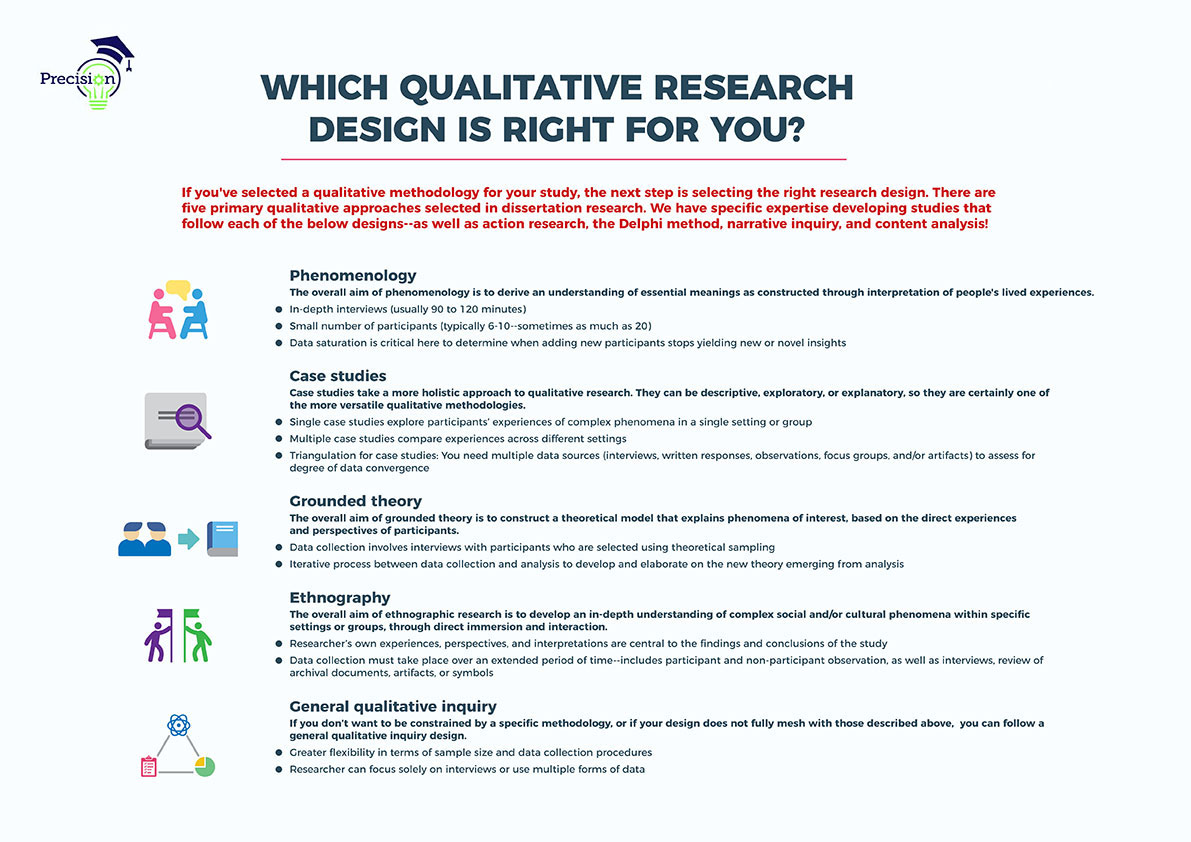

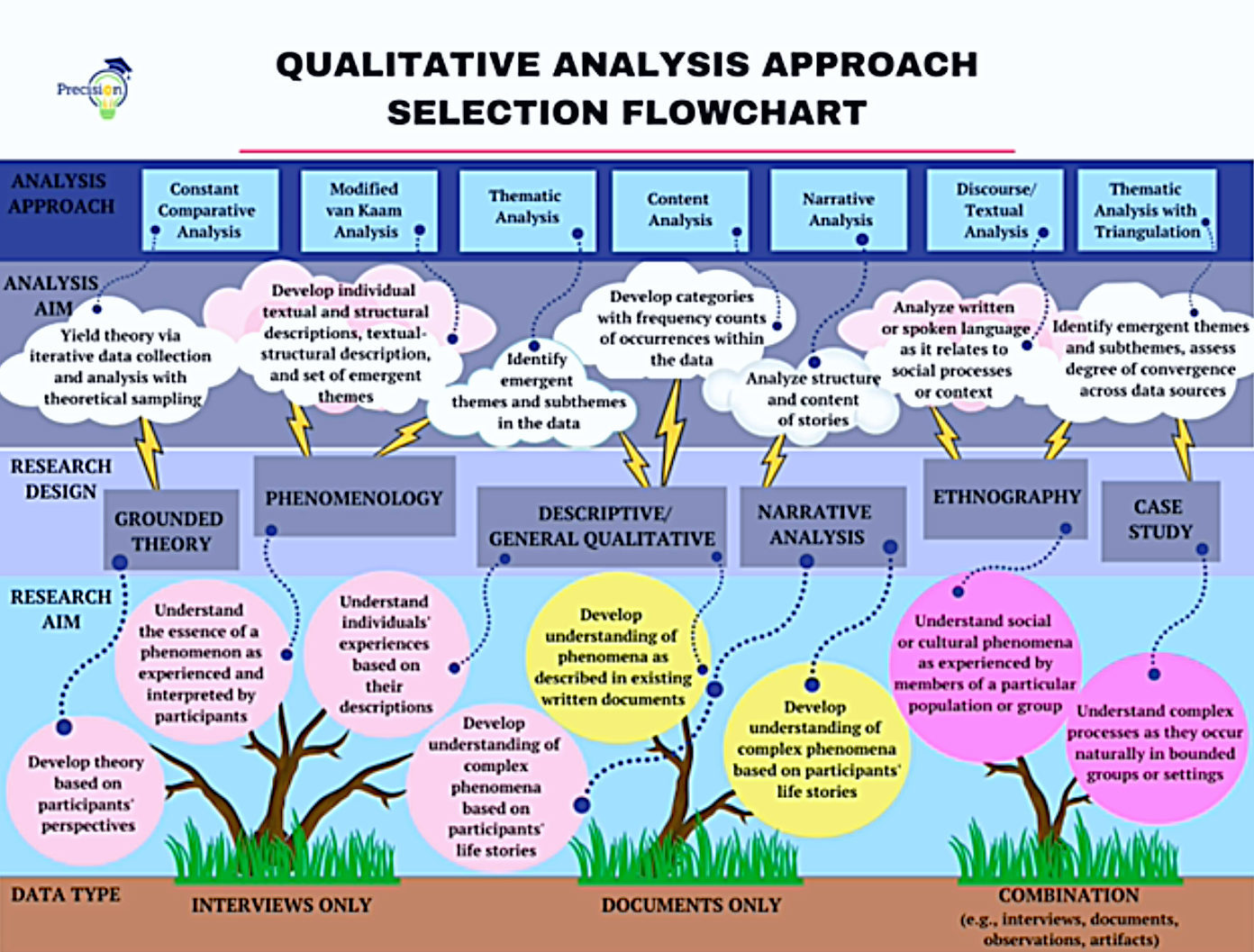

If you do think that a qualitative method would be the best choice for your study, the next step is selecting the right research design. There are five primary approaches taken in dissertation research: phenomenology, case study, grounded theory, ethnography, or general qualitative inquiry. Let’s look at them!

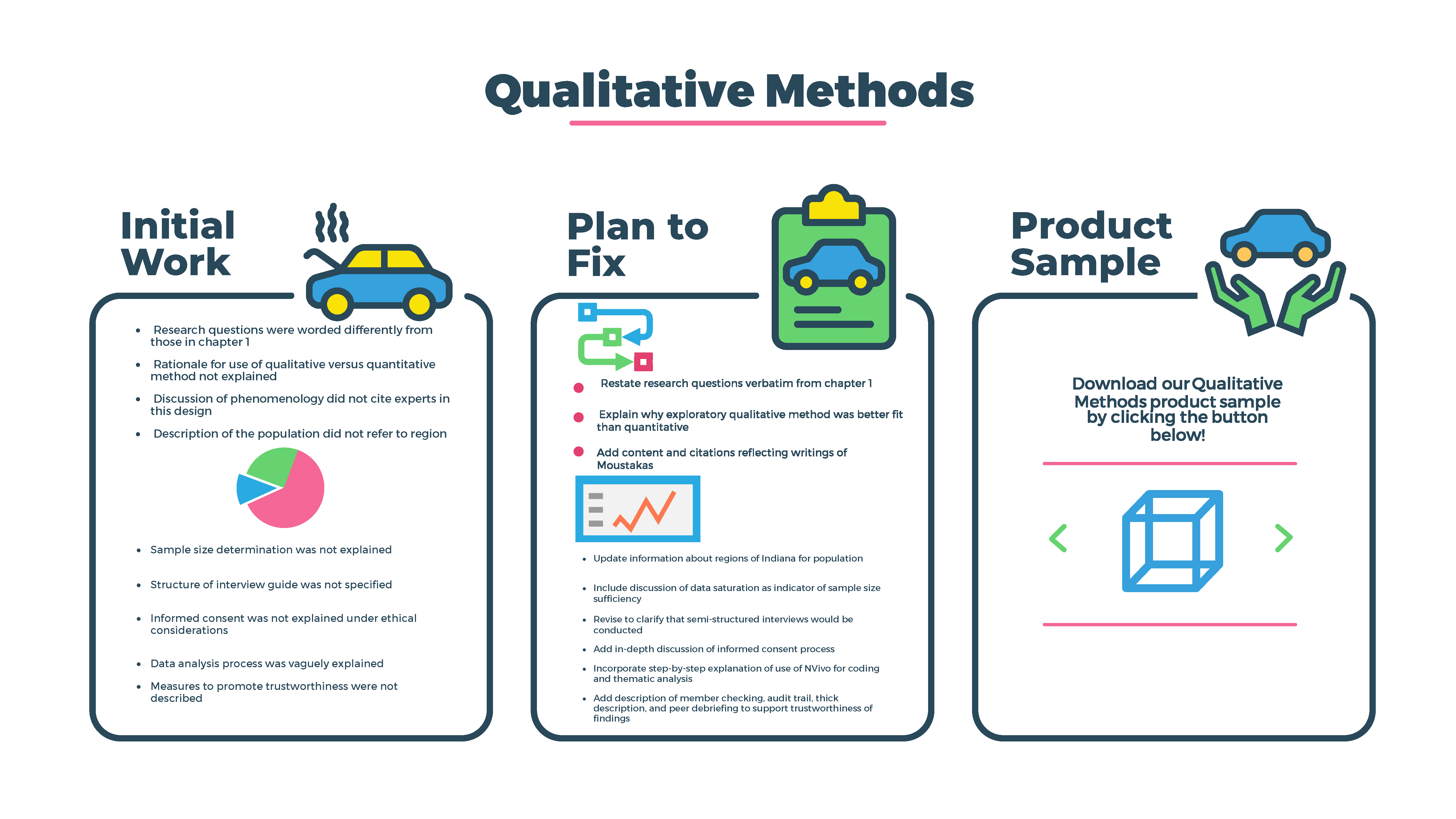

The overall aim of phenomenology is to derive understanding of essential meanings as perceived by participants, as these are constructed through interpretation of their lived experiences.

This methodological approach necessitates in-depth interviews that usually last from 90 to 120 minutes. Typically for doctoral-level research, phenomenological studies also have a small number of participants. These can be as small as 6 to 10, but some doctoral candidates decide to interview up to 20 participants. Generally, deciding how many participants to interview is based on estimation of the sample size needed to achieve data saturation. This is the point when adding new participants to your sample stops yielding new or novel insights into your research questions.

With phenomenology, there’s also an in-depth analysis process: For example, Moustakas’s 8-step modified van Kaam method, Giorgi’s modified Husserlian approach, or another interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) protocol. For the most part, these approaches require both textural and structural descriptions of participants’ experiences. A hugely important aspect of analysis in phenomenological studies is to stay “close to” the meanings as expressed by participants. This is because your aim in this design is discover how your participants make sense of and interpret their lives around specific questions. Without this commitment to stay close to their expressed meanings, you risk imposing your own bias over the data.

So, with our example of rural nurses and turnover, an appropriate phenomenological study would be to explore rural nurses’ lived experiences related to leaving their jobs and their perspectives on the factors that influenced their decisions to leave. We might then select a sample of 6-12 rural nurses who left their jobs through purposive sampling. This is a technique for ensuring that your participants have the necessary backgrounds, attributes, or experiences to respond fully to your research questions. Then, we would conduct in-depth semi-structured interviews with these nurses and conduct a van Kaam analysis to obtain our findings.

Now, case studies take a more holistic approach to qualitative research. The overall aim is to understand complex processes as they naturally occur within specified bounded systems or groups.

For a single case study, the aim is to explore participants’ experiences of complex phenomena in a single setting or group. For a multiple case study, the aim is to compare experiences across different settings, such as different business environments or schools.

Case studies can be descriptive, exploratory, explanatory, so they are certainly one of the more versatile qualitative methodologies.

A main consideration for data collection for case studies is triangulation. You need multiple data sources (such as interviews, written responses, observations, focus groups, and/or artifacts) to assess for degree of data convergence across sources.

As for analysis, this is quite complex for case studies. In-depth thematic analysis works well for this design since you’re working with multiple data sources. It is always important to conduct analysis to arrive at findings for each of your different sources of data, but then to also assess the degree of convergence across these data sources. This is the essence of triangulation across data sources, which brings such strength to the case study design.

Returning to our example, if you were to conduct a case study regarding rural nurses and turnover decisions, you might sample current and former nurses from a single rural hospital that has struggled with turnover in the last few years. Then you might conduct interviews to explore their thoughts on turnover, observations of working conditions in the hospital, and reviews of documents that might shed light on your research questions, like evaluations, training records, shift rotations, and so on.

And, since we’re talking about triangulation, I’ll just note that many online universities have particularly strict requirements for triangulation. We are well versed with these requirements because of our vast experience with all of the major online universities–so, we definitely know what you need in terms of dissertation help for this or any other aspect of your methodology discussion!

Moving on to grounded theory, the overall aim of this design is to construct a theoretical model that explains phenomena of interest and that is based on the direct experiences and perspectives of participants. Data collection involves interviews with participants who are selected using theoretical sampling, meaning they are deliberately chosen based on expectations of their abilities to “fill in” any gaps in understanding as you construct theory from the data.

Grounded theory involves an iterative process in which the researcher moves between data collection and data analysis, with insights gained through analysis phases then guiding the focus of future data collection. This iterative process then furthers the continued theoretical sampling process, as new participants are sought to elaborate more fully on as yet undeveloped components of the theory as these emerge through analysis.

Data analysis progresses from open coding through subsequent steps of axial and selective coding, involving a process of constant comparison of emerging categories of meaning within and across participant data.

A grounded theory study of rural nurses and turnover might aim to construct theory based on rural nurses’ perspectives that explains the links between any environmental deficits in professional development, lower levels of social support, low pay, and burnout, which then lead to turnover. The difference with grounded theory is the ultimate aim of constructing a theoretical model that can inform future research, as this study of rural nurses and factors that combine to influence turnover does.

Moving on, ethnography is a design whose overall aim is to develop an in-depth understanding of complex social and/or cultural phenomena within specific settings or groups, through direct immersion in and interaction with the setting or group of interest. This is a fundamentally immersive form of inquiry, in which the researcher’s own experiences, perspectives, and interpretations are central to the findings and conclusions of the study.

Data collection must take place over an extended period of time to develop a full appreciation of the cultural complexities as they occur within the group of interest. This is often a combination of immersive approaches such as participant and nonparticipant observation, as well as interviews, review of archival documents, review of artifacts or symbols that have relevance for the group of interest.

Data analysis may be conducted using a thematic analysis approach, and may also be conducted using the constant comparative approach often associated with grounded theory.

For our example of rural nurses and turnover, an ethnographic study would ideally involve a researcher who is also a practicing nurse or medical professional, who would use his or her own participation in nursing environments in a rural area to explore the reasons for turnover. These immersive experiences might then be supplemented by interviews with nurses and review of written narratives by nurses who had left their rural positions.

Finally, if you don’t want to be constrained by a specific methodology, or if your design does not fully mesh with those I’ve already described, you can use a general qualitative inquiry design. This design allows flexibility in terms of sample size and data collection procedures, and can focus solely on interviews or use multiple forms of data. For this design, a straightforward thematic analysis works quite well.

Conducting qualitative analysis can seem like an overwhelming task, but really, you do it every day. Making sense of your data using a language-based analysis is very similar to the ways you might interpret conversation or content shared through the media on an everyday basis. For example, in the current climate in the United States, if you hear someone talking about the importance of repealing the Affordable Care Act, you might make the assumption that this person is a republican. Whether you know it or not, this is a form of qualitative analysis you have just engaged in.

However, as you might be thinking, this was a mighty subjective interpretation you just made of this person based on what he or she said, and it could very well be incorrect. You obviously wouldn’t want to introduce such potential for erroneous conclusions in your qualitative analysis, and this is why incorporating procedures to promote trustworthiness is so important. Trustworthiness is the qualitative equivalent of reliability and validity in quantitative studies, and there are several methods for promoting it.

We’ve already talked about triangulation, which is one such procedure for building trustworthiness.

But you can also do things like peer debriefing, where you have a separate party review your ongoing coding and analysis to make sure you’re not making any undue impositions of bias over the data.

You can also keep an audit trail, which tracks all of your thoughts and decisions about the study and the analysis as you go along.

Member checking is when you verify your transcripts with participants to ensure accuracy.

And finally, thick description means you provide lots of information about the study setting, participants, and data to help the reader to assess how transferable your findings might be to other settings.

As you can see, putting together a qualitative study can lead to fabulously rich data that can answer research questions with an impressive degree of depth and variability. However, with the potential for subjectivity to erode the rigor of your findings, it is essential that you conduct your qualitative analysis in a systematic manner with safeguards to promote trustworthiness.

Fortunately, qualitative research is one of our core specialties, and if you feel like you’d benefit from talking to a dissertation consultant as you select your qualitative methodology for your dissertation, or finalize your analysis protocol, please don’t hesitate to reach out for assistance to one of our qualitative research specialists.

Thanks for watching!